Got Milk Crates? Why People Do Stupid, Dangerous Viral #Challenges

6 min read

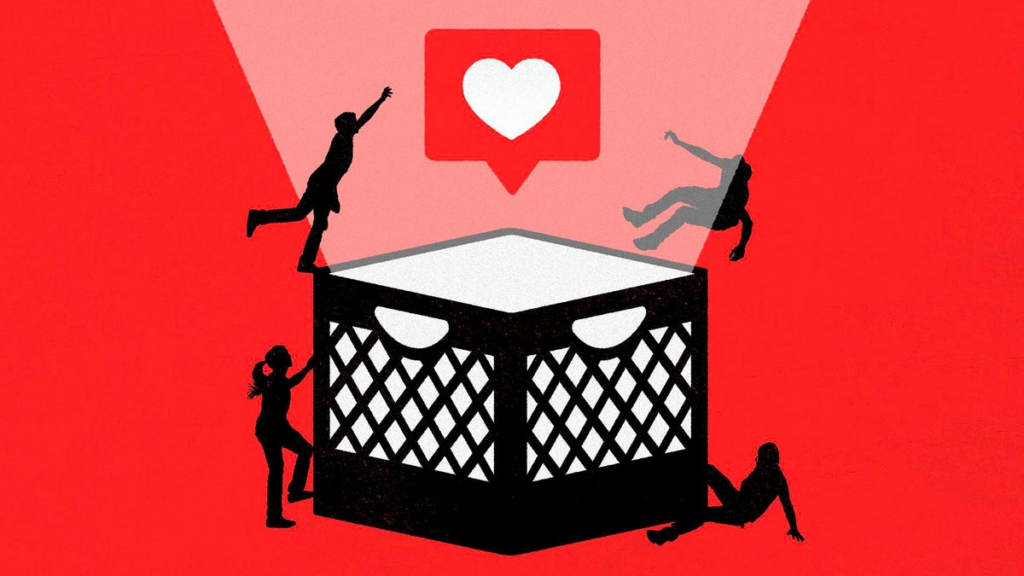

Social media is rife with people trying (and mostly failing) to race up rickety stacks of milk crates. A combination of youth, boredom and psychology is to blame.

Running up a perilously balanced pyramid of milk crates. Swallowing copious amounts of cinnamon, Benadryl – even laundry detergent. Another year, another viral “challenge.” This year, it’s the “Milk Crate Challenge,” which involves scaling a quivering mountain of plastic milk crates. But American Ninja Warrior, this is not. Most of the social media climbers end up in a bruised heap on the ground, or worse.

If the past is prologue, it’s likely dozens of people could end up in urgent care or hospital emergency rooms as a result of their milk crate climbing efforts. In the early 2010s, YouTube’s “Cinnamon Challenge” saw people try to ingest large amounts of dry cinnamon, earning nosebleeds and intense vomiting for their efforts. The Tide pod swallowing challenge of 2018 saw poison control calls in the month of January shoot up to 140, compared to 53 calls in all of 2017. The “Benadryl Challenge” of 2020, which involved taking such large doses of the antihistamine to cause delirium, prompted the FDA to issue a statement after a spate of hospitalizations and even some deaths.

Why do people engage in dangerous viral challenges that they know could cause bodily harm or even death? It is not a well-studied area but experts point to a range of factors, such as desire for social status, poor risk assessment and over-optimism that nothing will go wrong.

Historical stunt fad participants include these 35 college students crammed into a phone booth in 1959 and a 14-year-old who sat on a flagpole for 23 days in 1929.

AP Photo; Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing

As long as there’s an audience capable of providing near instant feedback, people will continue to snort, ingest and crash into fleeting viral stardom. This is especially true of TikTok, where 25% of users are between the ages of 10 to 19 years old, according to Statista, an age group that’s been lonely in the past 18 months thanks to remote school and fewer activities. “This is a very young audience. They want to be part of something now more so than ever, because they’ve been socially isolated,” says Corey Basch, a professor of public health at William Paterson University. “We know that people at younger ages don’t often don’t analyze the ramifications of their actions prior to taking part in an activity. They tend to be very impulsive, and I think this is especially true when their actions are being validated at such a high rate.”

Taking part in viral stunts and pranks is not exclusive to adolescents, but it’s more common because the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain responsible for decision-making — is still developing through the mid-20s, explains Joshua Liao, a physician and behavioral scientist at the University of Washington School of Medicine. It’s also a time of searching for connection with other people. “Social connection and status matters for everybody. But that life stage for many people it’s particularly important,” he says. So when people watch videos of their friends doing stupid things, they tend to follow the crowd because they see it as more “acceptable” behavior.

Dangerous, faddish stunts have a long history that precedes social media by many decades, if not centuries. In the 1920s, people sat on flagpoles for days or even weeks on end, sometimes falling — or even dying — in the process. In the 1930s, it became a fad to swallow live goldfish, a practice that seems innocuous but often left people with lingering parasitic infections. In the 1950s, teenagers would try to break records to see how many of them could fit in a single phone booth.

It doesn’t help that humans are notoriously bad at assessing risks, Liao adds. For example, from a statistical perspective, a person is much more likely to get in a car crash than a plane crash. However, most people perceive flying as more dangerous than driving because of the “dramatic nature” of air travel. Pair that with a tendency towards over-optimism. “We are prone to overestimate the chances that we’re going to have a good outcome, and we underestimate the chance we’ll have a bad one,” he says. When someone sets up the milk crates, they have a false sense of control compounded with over optimistic thoughts that while other people might fall, it won’t happen to them.

A California man attempting the milk crate challenge in August.

APU GOMES/Getty Images

Then there’s the very nature of a challenge, says Basch, as “it’s inviting users to take part in some type of contest and inspiring them to participate.” And this psychological predisposition to embarrass yourself on social media can be harnessed for good by offering “challenges” that feed the sense of exhilaration and connection without risking injury. Just as viral milk crate videos took off, so did the “Ice Bucket Challenge,” where people had buckets of ice water dumped over their heads to raise money for ALS. During the early days of the pandemic, a Covid-related handwashing challenge helped teach people the proper length of time to wash their hands.

Because of this history, Basch sees opportunity for public health professionals to embrace more of the communications tools that contribute to online virality — music, dancing, singing. “It doesn’t need to be grim and victim blaming and difficult for people to comprehend,” she says. “The easier and more fun we can make it the better, but there’s a line that we need to be sure we’re not crossing.”

She also says it’s the responsibility of the social media networks to discourage dangerous activities. TikTok agrees. “TikTok prohibits content that promotes or glorifies dangerous acts,” the company said in a statement. The hashtags #cratechallenge and #milkcrate no longer surface any videos and instead redirect to a blank page with TikTok’s community guidelines (though some users are attempting to flout the ban with hashtags like #cratestack). However, Twitter tells a different story. Milk crate videos continue to multiply on the platform and a spokesperson for the company said the hashtag and associated videos are “not in violation” of Twitter’s rules.

With the spread of the delta variant and rising Covid-19 cases across the United States, doctors warn it’s no laughing matter to end up in the emergency room as the result of a viral stunt, no matter how many likes you get for it.

“This is happening at a time where our national healthcare system is already strained from a global pandemic,” says Laura Welsh, an emergency medical physician at Boston Medical Center. “This is the time when providers are burnt out. They’re stressed. Consciously participating in something that poses inherent risks to your own health, you’re adding additional strains to a system that cannot support any more patients.”