What You Didn’t Know About Barkley L. Hendricks

6 min read

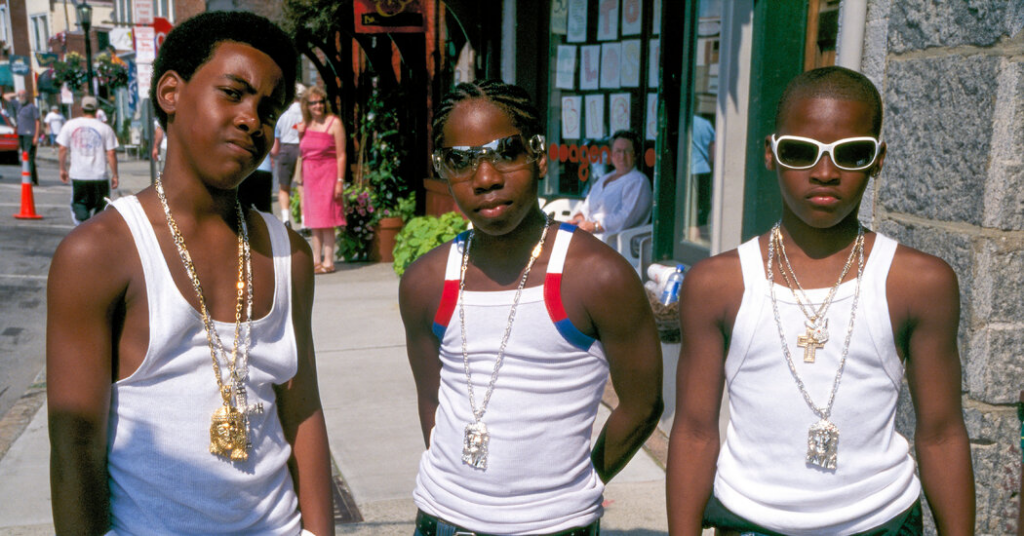

Barkley L. Hendricks portrayed Black people who exude attitude. “In the Black community, you stand out because you declare your own sense of identity beyond your environment,” said his longtime friend Richard J. Watson, artist-in-residence at the African American Museum in Philadelphia. “When you see yourself shown as a standout — and not because you haven’t eaten in three days and you’re a symbol of poverty — that gives you respectability.”

In the style of Manet and Velázquez, Hendricks painted full-length portraits of men and women who, with swagger and brio, project forcefully at a viewer. He typically painted his figures with overlaid washes of thin oil paint and set them against a monochromatic background that he applied in fast-drying acrylics.

But Hendricks, who died in 2017, was a photographer as well as a painter. This less celebrated side of his career is receiving deserved attention in a book, “Barkley L. Hendricks: Photography,” to be published early next month. It includes a relatively small selection of the unorganized trove of photos that he left in his home in New London, Conn., and which his widow, Susan Hendricks, and dealer, Jack Shainman, have been exploring and cataloging since his death.

Hendricks referred to his camera, which he habitually strapped around his neck before leaving home, as a “mechanical sketchbook.” But only a fraction of the thousands of photographs he took served as raw material for paintings. “The portraits he is best known for usually started with a photograph, which he would take liberties from,” said Trevor Schoonmaker, director of the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University in Durham, N.C., who in 2008 organized a retrospective exhibition of Hendricks’s paintings. “But the sheer volume of photographs that he shot over the years indicate that he was thinking of three things — models for paintings, subjects for inspiration, and third, he was also thinking of himself as a photographer.”

Hendricks had been taking photographs since adolescence. Growing up in tough North Philadelphia, he navigated his way through the violence-plagued neighborhood with the talisman of his camera. “Barkley would walk past a group of guys who looked like they would take your money, and they’d say, ‘Take my picture, man,’” said Watson, who, although also raised in North Philadelphia, didn’t meet Hendricks until they were fellow students at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.

Hendricks won a place at the academy through his talent as a draftsman, honing his skill there through hours of diligent drawing of plaster casts of ancient sculptures. When hanging out with friends, Watson recalled, Hendricks would see a gesture or stance that attracted his eye and he would say, “Take that card and hold it there for a second,” or “I like the way you hold a glass,” and snap a picture. To those who knew him, his photography seemed like a pastime tangential to his artistry.

But after graduating from PAFA, Hendricks in the early ’70s earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in fine art at Yale. As most of the painters there were abstractionists, he gravitated toward the work of an eminent teacher, Walker Evans, who ran the photography program. It seems that this was the point at which he realized that photography — only just emerging from second-class art-world status — could provide him with another way to express himself artistically.

“Barkley was always very adamant that while this was a process toward his painting, his photography was also something distinct in its own right,” said Anna Arabindan-Kesson, assistant professor of Black diaspora art at Princeton University, who has written extensively about Hendricks’s work. “It was his practice that he took photographs and worked from them. But I think they are in their own way finished works, because of his technical skill and eye. It was the way he learned to look at the world and understand the world.”

Some of Hendricks’s photographs might easily have become paintings, even many of those that never did. He customarily stopped strangers on the street to say he admired their style and ask if he might photograph them. His favorite models he photographed and painted frequently. George Jules Taylor, a sharp-dressing gay student at Yale who became a good friend, was painted by Hendricks four times, usually in stylish attire but once, just as flamboyantly, in a nude portrait from 1974 titled “Family Jules.” A photograph in the book, which Hendricks developed into a painted portrait in 1973, depicts Taylor in three-quarters profile and wearing a yellow striped shirt and broad-brimmed black hat, just as in the painting. But in the photograph, Taylor’s shadow on the wall adds another element, which in hindsight feels like a ghostly premonition of the younger man’s premature death.

When Hendricks traveled, he brought back copious records of what he had seen. One of the most striking photographs in the book depicts a man in Lagos, nattily dressed in a vivid pink suit. His immaculate attire contrasts sharply with the squalid shacks and puddles of filthy water that surround him. His long elegant fingers, self-assured pose and stalwart gaze reveal that he hasn’t let any of it touch him.

One of Hendricks’s longstanding subjects of fascination was women’s shoes, which he not only depicted but also collected. The subject lent itself more readily to photography than to painting. He snapped many, many pictures of feminine ankles and footwear — on sidewalks, rugs and television screens. A particularly artful black-and-white photograph reveals a woman’s calf and turned ankle, positioned against a rectilinear wooden desk. A studded chair subtly reinforces the fetishistic mood of the image. Schoonmaker thinks that the composition of such pictures is a link between Hendricks’s painting and photography. “The interest in cropping, formal balance, reflection and light are all there in the photographs,” he said.

Schoonmaker argues, too, that the humor that Hendricks displayed straightforwardly in his jokey painting titles but more discreetly in the actual paintings is often on the surface in the photographs. If he saw something that tickled his sense of irony, he would lift the ever-present camera to his eye and snap a picture. A seated dog at full attention is seen at the same level as the legs of his human counterparts. A wrecked jalopy sports a vanity plate of a Confederate flag. A billboard of a Black woman whose smile is more like a grimace bids, “Welcome! Kentucky Fried Chicken.”

“You get a more critical lens coming through the photography,” Schoonmaker said. “He’s more outward, observing life around him. In one photograph of a man who is presumably homeless, lying down on some steps, there’s a bathtub and a shopping cart. It’s social criticism, but it’s also humor and irony. He was a very keen observer of life.”

Hendricks’s camera also operated as a latchkey, gaining him entree to circles that might not have opened to him without it. A jazz enthusiast, he was able to photograph many of the masters, including Miles Davis and Dexter Gordon. The pianist Randy Weston became a good friend. In Nigeria he met with Fela Kuti, the Afrobeat pioneer, whom he greatly admired. He later memorialized Fela in a painting, holding a mike in one hand, grabbing his crotch and extending a burning cigarette with the other. Hendricks installed that portrait as an altarpiece above 27 pairs of high-heeled shoes.

It is likely that Hendricks will be best remembered as a painter, not a photographer. And while his painted subjects included Jamaican landscapes, geometrically balanced basketballs and hoops, and food from his pantry, the full-length portraits of commanding Black figures have exerted the greatest influence on the next generation of artists. His ambition was inspiring. “He told me when he went to London, he painted in front of the Van Dycks in the National Gallery,” Arabindan-Kesson recalled. “He said, ‘There’s a Van Dyck. Why can’t there be a Hendricks up there?’”

Although they are not groundbreaking in the same way, Hendricks’s photographs share his trademark wit and pride. Whatever the medium, his sensibility comes through. “The camera is just an instrument, the vehicle with which you express yourself at any time,” Watson said. “He is the operator — whether it’s a piece of chalk or a paintbrush or a camera.”